Our history is full of legends and these 11 popular history myths that are busted are just the tip of the iceberg.

Some of the history myths are quite insignificant and have little impact on the way we live our lives today. Did Queen Marie Antoinette really say “Let them eat cake” or not, doesn’t affect us in the slightest. The date of Christmas, however, is something that most people plan their lives around. It even affects the way the economy works, with big Christmas sales, trees, and decorations. And all of that because some guys arbitrarily decided that December 25th would be a good date to celebrate Jesus’s birthday.

Pixelbliss/Shutterstock.com

Other popular history myths, like Nero’s fiddle and Napoleon’s height, are the result of political slanders, created by their opponents. It is funny how we readily accept these myths as a genuine truth about great men, regardless of their origin. All it took was few caricatures published in London’s papers back in a day and Napoleon will forever be remembered as “La petite Caporal” (The Little Corporal). If you ask people on the streets today what happened at Austerlitz, chances are very few will know. But ask them how tall was Napoleon and most of them will start pointing at their chest, saying “Ye this big”. These history myths are even more persistent than science myths.

Some are created to boost pride and provide inspiration, like the 300 Spartans myth. While nobody in their right mind would question their bravery and loyalty, things didn’t go quite as we are led to believe by our history teachers. To make things even worse, they even made a movie and now we have people actually believing that Persians had monsters and mountain trolls in their army and that the Immortals were a mix between zombies and vampires. That’s Hollywood for you.

But for me personally, the myth about Polish cavalry charging at German tanks in World War Two was the most astonishing one. Why would anyone believe that? A cavalry charge with sabers and lances against armored vehicles? Yet, people believe in it, even today. Go figure.

If you want to know what really happened and see what other popular history myths are busted, read on.

11. The last invasion of Britain

The William the Conqueror invasion of England in 1066 was often portrayed as the last successful invasion of British Isles. This is, of course, a myth. In fact, just three years later, a large Danish army landed in Northern England and didn’t retreat until William coughed up some Danegeld to the invaders in 1070. But that was just the first one. In 1215, Prince Louis of France, the future King Louis VIII, invade England and took London. He was even proclaimed King of England (but not crowned). It took English two years and 10,000 marks paid to Prince Louise to make him leave. The next one to succeed in invading England was Henry Bolingbroke in 1399. He was crowned as King Henry IV in the same year. In 1485, it was Henry Tudor’s turn. After the invasion and victory at the Bosworth Field over Richard III (By the way, Richard didn’t say “A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!”, Shakespeare just thought it would be funny if he did) which ended the War of the Roses, he established the Tudor dynasty that reigned England until the 17th century. The last successful invasion of British Isles was conducted by William of Orange-Nassau in 1688. In the events that were later dubbed the Glorious Revolution, he defeated King James II at the Battle of Reading and was crowned as William III, 622 years after his namesake from Normandy crossed the English Channel.

10. The 300

You all know the story, the brave King Leonidas and his 300 Spartans stopped a million men Persian army at Thermopylae. Only, there weren’t just 300 Spartans (and there weren’t million Persians either, but that’s another myth) blocking the narrow passage. In fact, the Spartan contingent may be the smallest one among the Greek cities that formed an army 20,000 strong, according to modern estimates. For two days, the Greeks repelled relentless Persian attacks, causing huge casualties in King Xerxes’ army. Even the fabled Immortals, his personal guard, couldn’t penetrate the Greek phalanx. On the third day, Persian scouts, with the help from local shepherds, found a way around the Greek positions and started a flanking makeover. However, the Greeks found out and quickly retreated, avoiding encirclement. Now, this is where the myth originated. King Leonidas decided to stay back and fight a delaying action, to provide enough time for the rest of the Greek army to reach safety. The Oracle prophecy that he must die in order for Sparta to survive may have provided an additional motivation for Leonidas to choose a certain death. Now, this is where the things start to get really interesting. The 700 men strong contingent from Thespiae, a city near Thermopylae, knew that their home is lost if Persians make it through the pass, so they decided to stay as well. Being quite smaller than Athens or Sparta, their contingent represented every man of fighting age from their city, so their sacrifice is perhaps even greater than the Spartan one. 400 men from Thebes also choose to stay behind and face Xerxes. So, when Persians finally made it across the mountain, Leonidas had at least 1,500 men under his command. With the exception of few Thebans that surrendered, the rest of them were killed to the last man.

9. Magellan’s voyage

Ferdinand Magellan, the famous 16th-century Portuguese explorer, and the man after whom the Strait of Magellan is named for (and a penguin and couple of galaxies and a crater on Mars), is hailed as the first man to circumnavigate the globe. Except that he didn’t. First off, he didn’t set out to circle the globe, but rather to find a safer way for Spanish merchants to fabled Spice Islands. Magellan’s expedition is the first one to accomplish circumnavigation, but poor Ferdinand didn’t make it home, since he was killed by natives in the Philippines in 1521, about half way home. By modern standards, the expedition would be considered a disaster. It started with 5 ships and about 270 men. Only 18 of them aboard one ship, Victoria, made it home in 1522. Still, as an organizer of the expedition, Magellan received plenty of praises and is generally considered one of the greatest sailors and explorers in history.

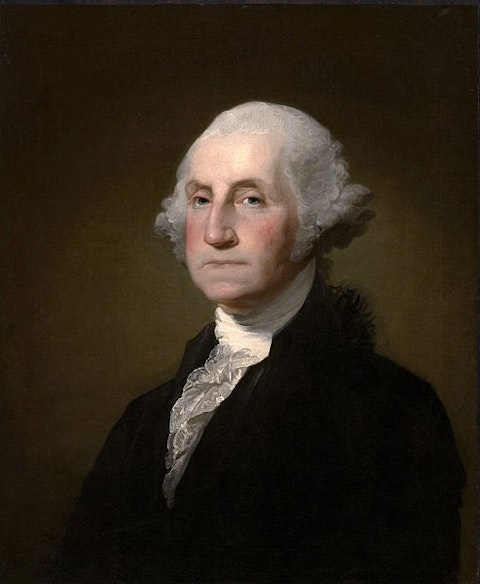

8. George Washington, the first president of these United States

In 1789, the United States held its first presidential election and, as expected, George Washington won every electorate vote. He is the only person to win the election unanimously, by the way, and judging by the way things are looking now, he will be for a long time. Just like we were thought in school, he is the first president of the US. Except for a tiny fly in that ointment. The United States were created in 1776, and Washington became president in 1789. Who was in charge during those 13 years, while he was chasing redcoats up and down the 13 colonies? Quite a few people, actually, starting with Peyton Randolph, who resigned after less than two months. Until 1781, the title was President of the Continental Congress. In 1781, The Articles of Confederation were passed, known as the Constitution before the Constitution and the title changed to the President of the United States Congress. All in all, 15 people were presidents before George Washington. He is just the first popularly elected president, not the first one ever.

7. Jesus’ birthday

Christmas is the most popular Christian holiday. On December 25th, we celebrate the birth of our Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ. (And we get gifts, drink eggnog and watch some NBA). This is because Jesus was born on Christmas, right? Wrong, actually. Nowhere in the Bible is December 25th mentioned as Jesus’s birthday. In fact, there are few clues in the Bible that reveal Jesus couldn’t have been born on that date. For starters, shepherds were out with their flocks, highly unlikely for winter. And second, his parents came to Bethlehem to register for a Roman census. It is hard to believe that Romans, ever practical, would schedule such an important event in winter. Early Christians suggested several dates for Jesus’s birthday, like November 13th or March 28. In the end, they all settled on December 25th, for one simple reason. It was on this date (or near to it) that several Pagan festivals were held, like Roman Saturnalia and Sol Invictus festival, as well as celebration in honor of Persian god of light Mithra. And yet, millions of people around the world celebrate this date, convinced by a clever ploy that was the day Jesus Christ was born.

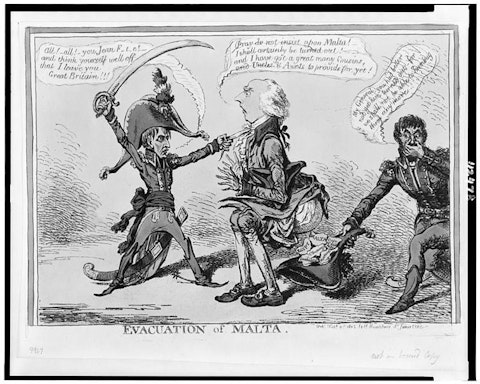

6. Napoleon, the little corporal

The prevailing image of Napoleon Bonaparte is that of a short, fat guy in pompous uniform throwing fits whenever things didn’t go his way. There’s even a psychological condition named after him, called Napoleon’s complex, because of that. The truth is he was 5’7’’, above average height for early 19th century, which was 5’5’’ in France. The myth probably originated because he was always surrounded by his guards in public, who were, like all guards, selected because of their physical appearance and were all taller than him. English propaganda welcomed the myth and did all in its power to spread it all over the world.

5. The Pyramids

When we think of how Egyptian pyramids were built, we imagine thousands of slaves pulling huge stone block up the ramps, with Pharaoh’s guards cracking whips around them. While there probably were some slaves involved, most of the work in pyramid construction was done by paid professionals. The pyramid builders took great pride in their work and were held in high esteem in Egyptian society. Their pay was 10 loafs of bread and a jug of beer per day. Total workforce involved in building the Great Pyramid could be as small as 30,000. The crews rotated on and off the construction site in shifts that lasted few months. Only a core of some 5,000 expert stonemasons and engineers were present during the whole operation. If anything, this makes pyramid building even more astonishing.

4. Nero’s fiddle

In 64AD a large fire that lasted for 5 days severely damaged Rome. Some Roman historians, like Suetonius and Cassius Dio, accused Emperor Nero of starting the fire and singing in costume as the city burned. However, it has been since proven that it is a rumor started by his political opponents. Nero was in Antium when the fire started, some 30 miles south of Rome. As soon as he arrived, he organized a large-scale relief effort, opening his palace to house people who lost their homes and even personally going through rubble in search of survivors. However, the rumor stuck and he needed someone else to blame, so he choose Christians, a popular scapegoat at the time. Christians get to meet the lions in the Coliseum, but the myth of Nero playing a fiddle persisted. By the way, the fiddle was invented some 1,000 years later, so it should be a lyre.

3. Viking helmets

Vikings were expert sailors and ferocious warriors who terrorized Europe for several centuries. Their fighting skills were in high demand, and even Byzantine Emperors hired them as their personal bodyguards, called the Varangians. So why would such experience warriors go to battle wearing horned helmets, which could be knocked off their head with a single blow? Well, they didn’t. Their helmets were traditional bowls with added nose protection and sometimes an eye protection. If anything, horns were reserved for ceremonial occasions and were never worn to battle. The myth originated in the 19th century when Wagner’s opera “Der Ring des Nibelungen” was staged in Berlin.

Costume designer Carl Emil Doepler thought it would be really cool to give his Vikings horned helmets and the image stuck to the point that even the Hägar the Horrible’s dog wears one.

Khosro/Shutterstock.com

2. Shot across the bow

At the height of the Cuban Missile Crisis, US Navy has established a cordon aimed at stopping the Soviet ships carrying nuclear missiles from reaching a small Caribbean island. According to the myth, ships came bow to bow and Americans fired a warning shot across the bow of the leading Soviet ship. At the last moment, Soviets chickened out, turned tails and ran home. In the white house, Dean Rusk, JFK’s Secretary of State uttered the words:” We are eyeball to eyeball, and I think the other fellow just blinked.”

Only it never came eyeball to eyeball. The Soviet ships received orders to return when they were approximately 750 miles away from US blockade line. That show across the bow would have been one of the finest examples of naval gunnery in history.

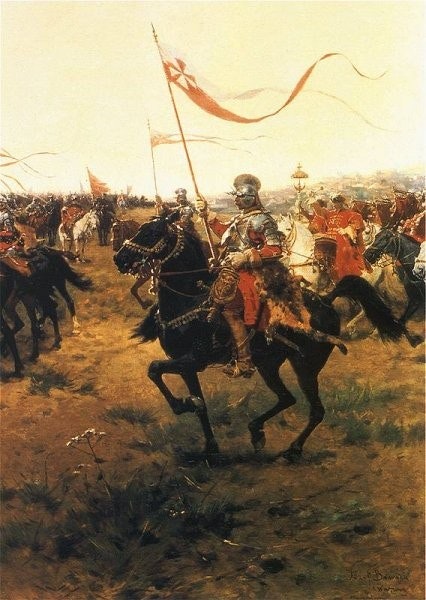

1. Polish cavalry charge

The image of a Polish cavalry charging German tanks in September of 1939 is ingrained in our collective memory as one of the most futile moves in the history of warfare. Apart from being extremely courageous (not to mention extremely stupid), it is also very untrue. The Poles didn’t charge tanks. When you think about it, who would in their right mind? What would they hope to achieve with lances and sabers against steel-armored vehicles? But at the time it was useful, as it propagated the need for resistance against one of the most efficient war machines humanity ever saw, regardless of how useless and counterproductive said resistance was.

The truth is that a unit of German infantry blundered near the positions of Polish Pomeranian Cavalry Brigade, near the village of Kroyanty. The brigade commander, Colonel Adam Zakrzewski, saw the opportunity for his, by then obsolete unit, to inflict some damage to the hated enemy, so he ordered his 18th Uhlan Regiment to attack them. Uhlans quickly routed infantry in the open, but as soon as they were done, a German recon unit, consisting of light armor, appeared and started mowing them down with heavy machine gun fire. The Poles retreated, losing about 25 dead and twice that many wounded. The Germans were so impressed with the action that they were even considering a tactical retreat in the sector.

The day after the battle, Germans brought was correspondents to the site. One of them, an Italian Indro Montanelli, seeing the dead horses and Polish cavalrymen among tank tracks, wrote a piece about a cavalry charge that gave rise to the one of the most popular history myths.