The Bad Guys win!

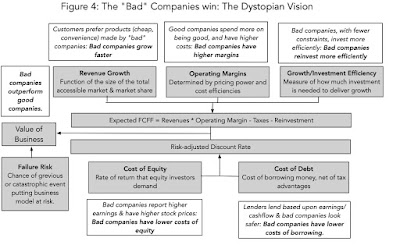

With regard to promoting social responsibility, the “bad behavior gets punished” scenario is not as good as the virtuous cycle, because it will tend to scare companies away from being “bad”, rather than induce them to be “good”, but it is still better than a third and potentially devastating scenario for ESG advocates, where bad companies are rewarded for being bad, and become more valuable than good ones:

In this scenario, bad companies mouth platitudes about social responsibility and environmental consciousness without taking any real action, but customers buy their products and services, either because they are cheaper or because of convenience, employees continue to work for them because they can earn more at these companies or have no options, and investors buy their shares because they deliver higher profits. As a result, bad companies may score low on corporate responsibility scales, but they will score high on profitability and stock price performance.

The Evidence

The question of which of these three scenarios is the right one is not one that can be settled by logic or with anecdotal evidence, but with data. For more than two decades now, researchers have examined the link, with the following conclusions:

- A Weak Link to Profitability: There are meta studies (summaries of all other studies) that summarize hundreds of ESG research papers, and find a small positive link between ESG and profitability, but one that is very sensitive to how profits are measured and over what period, leading one of these studies to conclude that “citizens looking for solutions from any quarter to cure society’s pressing ills ought not appeal to financial returns alone to mobilize corporate involvement”. Breaking down ESG into its component parts, some studies find that environment (E) offered the strongest positive link to performance and social (S) the weakest, with governance (G) falling in the middle.

- A Stronger Link to Funding Costs: Studies of “sin” stocks, i.e., companies involved in businesses such as producing alcohol, tobacco, and gaming, find that these stocks are less commonly held by institutions, and that they face higher costs for funding, from equity and debt). The evidence for this is strongest in sectors like tobacco (starting in the 1990s) and fossil fuels (especially in the last decade), but these findings come with a troubling catch. While these companies face higher costs, and have lower value, investors in these companies will generate higher returns from holding these stocks.

- And a link to Failure/Disaster Risk: An alternate reason why companies would want to be “good” is that “bad” companies are exposed to disaster risks, where a combination of missteps by the company, luck, and a failure to build in enough protective controls (because they cost too much) can cause a disaster, either in human or financial terms. That disaster can not only cause substantial losses for the company, but the collateral reputation damage created can have long term consequences. One study created a value-weighted portfolio of controversial firms that had a history of violating ESG rules, and reported negative excess returns of 3.5% on this portfolio, even after controlling for risk, industry, and company characteristics. The conclusion in this study was that these lower excess returns are evidence that being socially irresponsible is costly for firms, and that markets do not fully incorporate the consequences of bad corporate behavior. The push back from skeptics is that not all firms that behave badly get embroiled in controversy, and it is possible that looking at just firms that are controversial creates a selection bias that explains the negative returns.

In summary, based upon the studies so far, the strongest evidence in support of ESG seems to be that “bad” companies face higher funding costs (from debt and equity), whereas the evidence on ESG paying off as higher profits and growth is elusive. There is some evidence supporting the proposition that being socially responsible (or at least not being socially irresponsible) can protect companies from damaging disasters, but selection bias is a problem.

ESG and Returns

To begin with, the notion that adding an ESG constraint to investing increases expected returns is counter intuitive. After all, a constrained optimum can, at best, match an unconstrained one, and most of the time, the constraint will create a cost. In one of the few cases where honesty seems to have prevailed over platitudes, the TIAA-CREF Social Choice Equity Fund explicitly acknowledges this cost and uses it to explain its underperformance, stating that “The CREF Social Choice Account returned 13.88 percent for the year [2017] compared with the 14.34 percent return of its composite benchmark … Because of its ESG criteria, the Account did not invest in a number of stocks and bonds … the net effect was that the Account underperformed its benchmark.” In fact, there is an inherent contradiction, at least on the surface, between the argument that ESG leads to higher value and stock prices, made to CEOs and CFOs of companies, and a simultaneous argument that investors in ESG stocks will earn higher (positive excess) returns, by investing in these companies.