Linn Energy LLC (NASDAQ:LINE)’s current predicament is a conservative investor’s worst nightmare. This is after all, a company often bought for long-term income and preservation of capital. Linn sports an excellent track record of value creation, but keeping up growth is becoming more and more of a challenge. Recent events starkly highlight the depth of that problem. One obvious cure for what ails Linn Energy LLC (NASDAQ:LINE) is closure of the Berry Petroleum Company (NYSE:BRY) deal. Unfortunately, dollars shed from LinnCo LLC (NASDAQ:LNCO) shares make that deal look more and more tenuous by the day. Absent Berry Petroleum Company (NYSE:BRY), Linn faces serious challenges.

Posts, blogs and articles regarding the accounting peculiarities at the center of this maelstrom litter the Internet. However, relatively few focus on the immediate cause of Linn Energy LLC (NASDAQ:LINE)’s predicament. That seems to have been lost in the tide of articles passionately debating the legitimacy of Linn’s non-GAAP put accounting.

It’s as simple as the numbers.

Linn Energy LLC (NASDAQ:LINE)’s real problem is more mundane and perhaps more serious than the sensationalized accounting controversy. At the heart of the matter is a straightforward hedging deficiency. That’s ironic for a company that’s hedged more fully than any of its peer group.

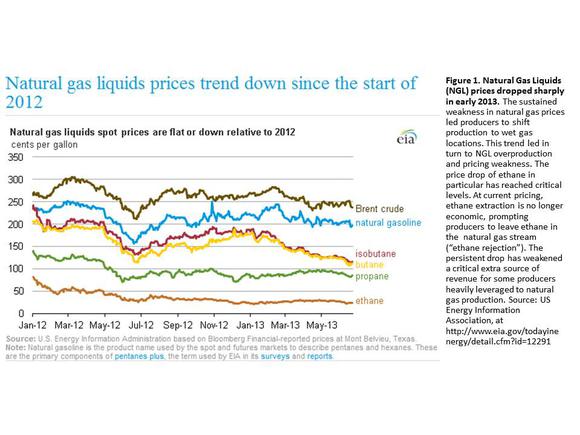

In a nutshell, the problem is that natural gas liquid (NGL) prices collapsed on Linn Energy LLC (NASDAQ:LINE) (see Figure 1 for a recent price chart of NGL constituents). Hedging NGL prices is more complicated than natural gas and oil. It requires separate contracts for individual hydrocarbons and few upstream producers bother given the complexity. In the absence of NGL hedges, a collapse of ethane prices caught Linn with its pants around its ankles.

NGLs were a godsend for the large natural gas producers of the mid-continent (mid-con) region like Devon and Chesapeake. As natural gas prices cratered, drillers shifted rigs to wet gas locales that were still profitable given the liquids they produced. Just like the larger independents, Linn ramped its liquids production on the back of solid results from its mid-con Granite Wash acreage. Much of that liquids growth came in the form of NGLs and not oil.

The Nat Gas solution bred an NGL problem.

Gas wells are “wet” when they’re relatively rich in larger alkanes. When natural gas is processed, any larger alkanes are removed and sold separately. These larger alkanes (ethane, propane, butane, isobutane and pentanes) are collectively reported as NGLs by producers. Value added through fractionation is significant.

While NGLs boosted revenue at a badly needed time, in many ways producers just kicked the can down the road. What began as a dry gas oversupply blossomed into an NGL oversupply. Ethane supplies in particular have reached critical levels, as Linn and others now face ethane rejection.

It takes energy to fractionate natural gas. At some point, it becomes economically infeasible to extract ethane if prices can’t support that cost. When this critical price is reached, processors stop removing ethane from the gas stream, extracting only larger hydrocarbons. Current pricing puts us in this ethane rejection territory, an environment that’s persisted since the end of 2012. That has producers feeling the pinch.

For Linn, the problem exhibits itself in two ways. The first is that rejected ethane is lost to the gas stream, cutting NGL production levels. That’s a contributing factor to Linn’s reduced Q2 NGL numbers. NGL production was off 6% from the linked quarter (see Figure 2A). Second, lower pricing dragged revenue down yet another notch.

While Linn derives only a small portion of its revenue from NGLs, their contribution remains significant (see Figure 2B). Its importance becomes clear when you consider the size of the hole in Linn’s coverage ratio. The single most germane issue brought up by shorts is that Linn’s distribution exceeds its own distributable cash flow metrics. In Q2, Linn paid out $170 million to unitholders, but recorded only $152 million in distributable cash flow (DCF). That’s an $18 million shortfall.