Hedge fund manager John Paulson made billions betting against the housing market. You’ve probably heard the story.

Less well known is where Paulson got the idea that housing was a bubble. Wall Street Journal Greg Zuckerman reporter Greg Zuckerman describes the epiphany in his book, The Greatest Trade Ever Made.

Here’s what happened.

In the middle of last decade, Paulson and one of his analysts, Paolo Pellegrini, had a feeling housing was overheated. But not everyone agreed. Only in hindsight is it screamingly obvious.

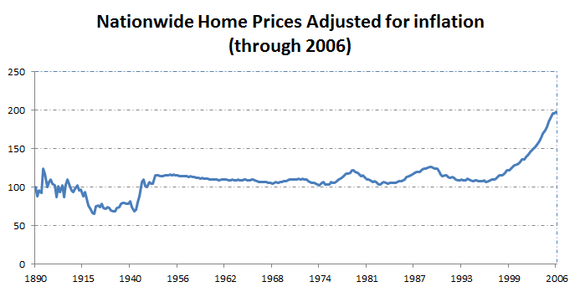

Paulson wanted Pellegrini to really prove prices were a bubble. Late one night in 2006, Pellegrini put together a chart of housing prices adjusted for inflation over time. It probably looked something like this:

Source: Robert Shiller.

“The answer was in front of him,” Zuckerman wrote. Housing prices flatlined after inflation for most of the last century. Then, early last decade, they zoomed higher.

“The upshot,” Zuckerman wrote, “U.S. home prices would have to drop by almost 40% to return to their historic trend line.”

Which is eventually what they did.

Paulson had deep knowledge of the mortgage market, but the core of his housing thesis rested on a basic concept: reversion to the mean. It’s the simple idea that, as investor Dean Williams once put it, “something usually happens to keep both good news and bad news from going on forever.” Big outliers tend to be short-lived. Crowds don’t tolerate excess, so something happens to pull outliers back toward a happy medium. Averages act like gravity.

Reversion to the mean is probably the second most powerful law in finance, behind compound interest. Booms follow busts and busts follow booms. It happens over and over again, in all kinds of fields from finance to business to biology to physics.

Here are eight trends detached from their long-term average that should revert to the mean.

1. The percentage of workers who want full-time work but can only find part-time hours.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Millions of workers who want full-time work were pushed to part-time hours when the financial crisis hit in 2008.

The trend is getting better, with workers labeled as part-time for economic reasons falling for the past three years. It’ll probably keep reverting to the mean as businesses that slashed payrolls struggle to expand. Take this recent story about Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (NYSE:WMT):

Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (NYSE:WMT), the nation’s largest retailer and grocer, has cut so many employees that it no longer has enough workers to stock its shelves properly, according to some employees and industry analysts. Internal notes from a March meeting of top Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. (NYSE:WMT) managers show the company grappling with low customer confidence in its produce and poor quality. “Lose Trust,” reads one note, “Don’t have items they are looking for — can’t find it.”

This can’t last. So it won’t. Returning to average would push more than a million part-time employees back into full-time work.

2. New home construction.

Source: Federal Reserve.

We’re not building enough homes to keep up with household formation. We’ve been able to get away with this for a few years because we built too many homes during the housing bubble. But that excess is soaked up, and now we’ve gone the other direction, with the supply of for-sale homes at the lowest level in years. New home construction will very likely need to double from current levels sometime in the next decade to keep up with household formation.

3. Corporate profits.

Source: Federal Reserve, Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Three things happened to big businesses over the past decade: Technology allowed them to cut workers, interest rates fell, and rapidly growing markets like China and Brazil opened vast new markets to do business. Combine the three, and profit margins — the percentage of each dollar of sales that goes to profits — surged to an all-time high.

Profit margins have always mean-reverted. We don’t know when, and we don’t know what will drive margins lower — maybe higher wages, maybe higher commodity prices — but you can be confident they will. (Importantly, this isn’t necessarily bad for stocks.)

4. People and businesses investing in their future.

Source: Federal Reserve.

When the economy slows, businesses cut back on investment. When businesses cut back on investment, fewer people are employed. When fewer people are employed, the economy slows. When the economy slows, businesses cut back on investment. It’s a vicious cycle. But it eventually ends. Investment in factories and buildings as a percent of GDP fell to an all-time low in 2010. At some point structures need serious investment just to maintain business operations, at which point fixed investment rebounds. It’s already done that, but we’re still well below normal.